This is a reflection I wrote a couple of years ago for Creationtide.

When I was asked to prepare this reflection, I have to tell you my heart sank. It sank because caring for creation is a painful subject for me, and I knew it would be a struggle to find the right words. In the end, I decided to simply share with you where I am up to on the journey. These are not fully formed thoughts, and you may find me unnecessarily pessimistic, so please bear with me as you join me in this process of coming to terms with what is happening to our beautiful home planet.

The home I grew up in had a big garden that my father cultivated, and nearly all the vegetables and fruit that we ate were home-grown. We kept hens and ducks for eggs and had two geese named ‘Easter’ and ‘Christmas’. We foraged for firewood and picked hedgerow blackberries to make jam. I spent a lot of my time outside, although not always willingly, on the swing under the weeping willow, raking leaves, and growing radishes in my own little patch of earth.

Fast-forward several decades, and now I have my own garden. If anything, my love of nature has grown, and it is in nature that I perceive God most clearly. The breath of God that gives life to us also permeates the rest of creation. The earth and everything in it is sacred, because God inhabits it. I find our destruction of nature distressing because I love it for its own sake and because it reveals God to me.

Things have come to a head this summer [2023], with the wildfires and the flooding, and with the heatwaves and drought that have affected us here, with crops dying in the fields in my own village. I have had to find a way to cope with this and with the multiple other existential threats we are facing.

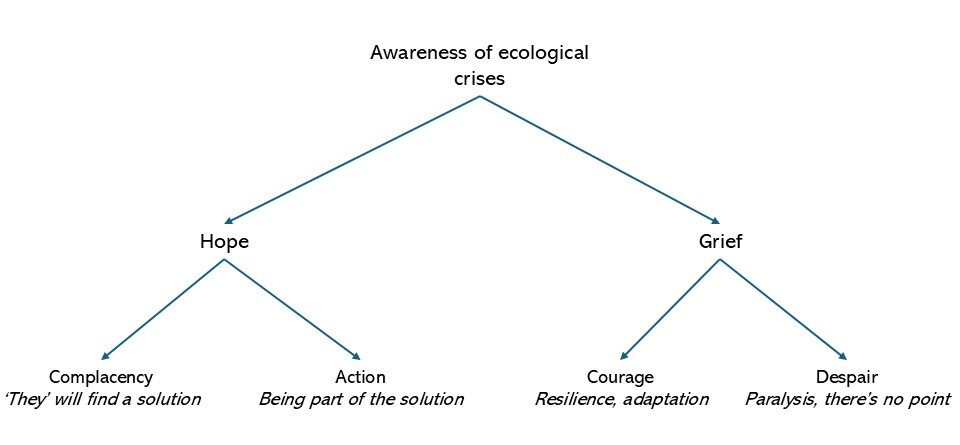

I suggest that each of us stands somewhere on the spectrum between denial and despair when it comes to the future that probably awaits us, or if not us, then certainly our children and grandchildren.

I’m left asking where God is in all this? How can God stand by and let us destroy everything, surely he’s going to intervene? But where was God during the recent floods in Pakistan? Or during the holocaust? Or during the Black Death? Or during numerous other catastrophes in human history? Many civilizations have even collapsed, because something in the human psyche means that we are unwilling to live within the sustainable bounds that God has set for us. But this time, it’s happening on a global scale.

We can’t assume that God will lift us out of our current crisis, and, given the way we have responded up to now, I don’t think that we can assume our governments or scientists will be able to save us either. At this point, I turn to the cross: faith needs to connect with the wounds of Christ as the beauty of the world fades.

Through Christ’s death on the cross, God identified with our suffering, with the suffering of all people and of all creation. In the death of Christ, human sin killed the incarnate God; in destroying creation, our sin is killing another revelation of God. But just as Christ rose to new life, so there is hope for the resurrection not just of humanity, but of all creation.

Our second reading today gives us an image of what that will look like, a new heaven and a new earth, the new Jerusalem, where God will make things whole again. Of course, this is symbolic language, but it gives us profound hope for the ultimate future of creation.

In the meantime, we have some choices to make. For those of us in denial, will we face reality, or will we continue to pretend it isn’t happening? And if we aren’t in denial, will we choose to trust God anyway or will we succumb to despair?

These times call for a deep, deep trust in God for who he is, not because of what he might do. We cannot expect God to save us from the consequences of the mess that we have created, but we can trust that God is good.

We cannot expect that our offspring will be saved from suffering, think of all those millions across the globe who are already suffering and whom God cares about just as much as about our children, but we can trust that God loves them with an eternal love.

We cannot assume that there will be a happy ending for planet earth as we know it, but we can trust that God holds its future in his hands. Christ is the alpha, the omega, the beginning and the end, all things have been created through him and in him all things hold together. (Colossians 1, Revelation 21). Let us step out of denial and out of despair and step into trust.

The writer of our psalm today speaks of this sort of trust in God, he wrote:

we will not fear, though the earth should change,

though the mountains shake in the heart of the sea;

though its waters roar and foam,

though the mountains tremble with its tumult.

And the psalmist encourages us to Be still, and know that I am God! And keeps repeating the refrain:

The LORD of hosts is with us;

the God of Jacob is our refuge

Student of Thomas Merton and clinical psychologist James Finley put it well when he said, ‘If we are absolutely grounded in the absolute love of God that protects us from nothing even as it sustains us in all things, then we can face all things with courage and tenderness and touch the hurting places in others and in ourselves with love.’’

Where God is in all this? God chooses to work through his people, those who live according to the values of the kingdom that Jesus preached.

In our first reading this morning, the Roman Christians are told to love their neighbours as themselves. And Jesus upped the ante by challenging us to love our enemies. So, by our words and by our deeds we are to love those who are suffering the effects of the climate crisis, and to love those who are actively making it worse, and that includes ourselves.

We aren’t given a list of rules about how to behave (although there are lists of ways to tread more lightly on the earth, which can be a good way to start); this command to love is about metanoia, that deep conversion of our hearts, minds and lives. Let me give you a simple example.

When I had my first child, I was determined to use cloth nappies for the sake of the environment. I was doing that quite happily, when a friend pointed out that perhaps I didn’t need to throw out disposable nappy liners that weren’t soiled, but that I could wash them and use them again – that conversation started me on a journey of questioning every disposable paper product that I used. For a start, I cut up old t-shirts to make baby wipes and have continued making changes ever since.

Our small actions might not avert environmental collapse, but we are to do our best to live lightly on the earth in response to Christ’s call to love our neighbours – both the neighbours that we come into direct contact with and those neighbours that we will never see and are barely aware of. However, the effects of our actions on our neighbours are not always immediately obvious. For example, when I buy a t-shirt, can I be sure that it hasn’t been dyed with toxic chemicals by an underpaid worker without protective equipment halfway across the world? How do I know whether my pension fund is invested in profitable, yet earth-killing, industries?

These sorts of questions can get so big and so numerous that they rapidly become overwhelming, tipping us back towards denial or despair. I deal with this by dividing up my worries into two lists – those that are rightly my responsibility and those that I leave to God. The things that stay on my list are the ones that I have some sort of power over. I can choose to eat less meat and dairy products, I can choose not to put insecticides on my struggling brassicas, I can choose to take the train instead of driving and so on. Of course I often fail, but God knows my heart and his grace is more than enough. But the fate of creation is most definitely on God’s list.

I am left holding the question of how to deal with the grief I feel. With great love comes with great pain – isn’t that the message of the cross? In the words of the hymn ‘did ere such love and sorrow meet, or thorns compose so rich a crown?’ I can’t help feeling that it is right that I feel this sadness, that I confess my part in causing it and ask for God’s grace to change my way of thinking and behaving – to ‘repent’. That I learn the language of lament. You might not be in that place right now, but I invite you to consider stepping into it – and to trust that God will meet you there.