This is a reflection on Luke 24:36-53 for Ascension day

I was a very impatient child and always in a rush. My mother would repeatedly say to me ‘more haste, less speed’, and I was covered in so many bumps and bruises from doing things too quickly that my dad worried social services might come round to find out what was going on. That impatient part of me was brought up short by one short phrase in verse 45 of today’s gospel reading.

Luke recounts Jesus’ last interactions with his disciples. He spoke peace over them, encouraged them to have faith and showed them the wounds on his hands and feet. But, for the disciples, the news that Jesus was alive was too good to be true and they struggled to believe. Jesus had to go as far as snacking on a bit of fish to convince them he wasn’t a ghost. These disciples are not exactly what we might consider to be role models of faith. Yet, despite this, v45 tells us that Jesus ‘opened their minds to understand the scriptures’.

I find it fascinating that while Jesus had spent three years with his disciples and had ample time to open their minds, that he didn’t do so until after the trauma of the passion, and just as he is about to leave them. Why did he wait until then? If only Jesus had kick-started this process of revelation much earlier, think how much better prepared the disciples would have been for their subsequent mission, how much pain they could have been spared if they’d known that the crucifixion was only a temporary setback, and how much conflict from theological disagreements could have been avoided over the millennia. It would have given the disciples time to digest the information, ask questions and get everything properly worked out while they could still check the details in person with Jesus.

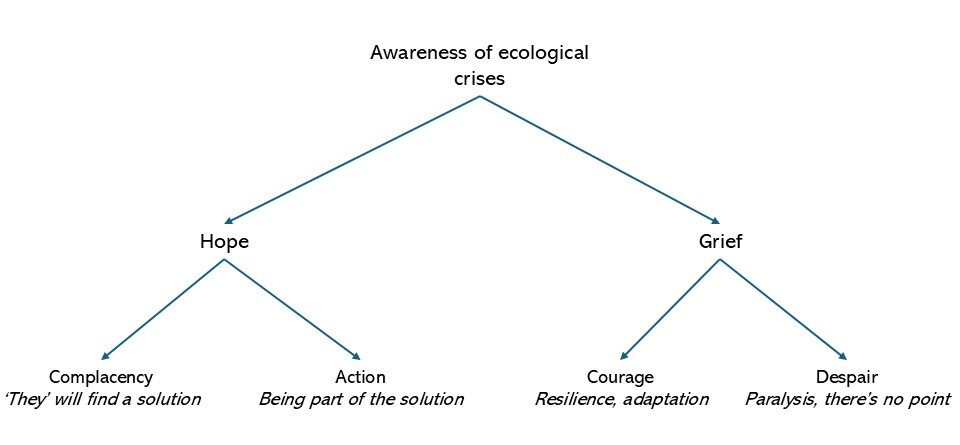

But these questions of mine are framed within a particular mindset that focuses on learning, achieving and making progress as rapidly as possible; while Jesus had a different purpose in mind. We strive for knowledge and power, look at how we are embracing artificial intelligence, assuming that if just we put our collective brains together we can solve the world’s problems; while Jesus let his disciples walk a path of ambiguity and pain. Our impatient mindset has resulted in something known as the ‘great acceleration’, the rapid and widespread increase in human activity which began around the mid-20th century and is having a devastating impact on the Earth’s natural systems.

The great acceleration is illustrated by a series of exponential graphs – with a shallow gradient until the 1950s, that shifts to a sudden and dramatic increase in recent years – and this holds true for many factors, ranging from the global population and plastic production, to ocean acidification and telecommunications. The impact of our ‘progress at any cost’ mindset on our planet and her inhabitants is catastrophic. We have used our knowledge and discoveries to bring about massive and rapid change, much of it arguably for the good, yet we have done this without wisdom and without insight into the potential unintended consequences.

This is so different from the way that Jesus worked with his disciples. Rather than ensuring they learned, achieved and made progress as rapidly as they possibly could, Jesus let the disciples go though through the drama of the passion before he opened their minds. During the passion, the disciples went on their own journeys of failure, betrayal, loss, grief and confusion. Post-resurrection, their faith and hope were rebuilt slowly, and, rather than being announced with trumpet blasts and choirs of angels, the resurrection itself was met with disbelief and soldiers whose silence could be bought with a few coins. Even as he opened their minds to understand the scriptures, Jesus emphasized his suffering, saying ‘The messiah is to suffer and to rise’ and when He blessed them, he did so by lifting up his wounded hands – a visual reminder of his suffering. This painful process is incompatible with any route to success that our society can imagine.

Jesus’s whole ministry was full of ambiguity, hyperbole and parables, he certainly didn’t teach in straight lines, perhaps partly to avoid us ever being too sure about what he was saying – to keep us humble and teachable? And giving the disciples the understanding they needed at the last possible moment seems entirely in character with this!

Had Jesus opened their minds earlier, these insights might have prevented them from humbly engaging with the message of the Gospel. With the ‘answer’ in their pockets, without having failed so catastrophically themselves, and without then fully engaging with Jesus’s suffering and death, they might have too easily distorted the message from a place of self-satisfaction.

Which is what, I fear, the church has done many times throughout the centuries. From a position of certainty and strength, we have forced Christianity upon others, causing all manner of damage in the process. But failure, humility and grace is a red line throughout the Scriptures. One of our earliest role models, St Paul, is someone who first had to get everything very badly wrong, ruthlessly persecuting the early church, before he was ready to become arguably the most influential Christian of all time – he had that touchstone of his own total failure, coupled with grace given by a God who knows what it is to suffer.

It might also comfort us to know that those who walked with Jesus himself had to go through the threshold of suffering – since Jesus didn’t spare his beloved friends, we shouldn’t expect him to spare us either. Rather than asking why we are suffering as if it were an aberration, might we come to accept it as a normal part of life to be faced and even embraced as the material we have to work with in this moment?

For example, the material my daughter had to work with over the last few years has come in the form of two very difficult bouts of depression. Looked at through the lens of capitalism, this experience was nothing but an unfortunate set-back to her career that rendered her less ‘successful’ and less able to produce, consume and generally keep the system going. However, she was forced to engage with this material to find a way forward, and although she wouldn’t wish depression on anyone and certainly doesn’t ever want to go through it again, the work she had to do to get healthy again has helped her to become more true to who she really is.

There is so much unnecessary suffering in the world that seems to serve no purpose. And just as we struggle to accept the suffering in our own lives, the suffering woven into the very fabric of creation is a great mystery. Consider the parasitoid wasp, who lays its eggs inside the body of a living caterpillar. These hatch and feed on their living host until the day they paralyze it and bore their way out through its skin to escape. Or consider the cuckoo who hatches in other birds’ nests and pushes its rivals out to their deaths. As Tennyson wrote in his poem In Memorandum, Nature is red in tooth and claw.

But St Paul seems very at home with the idea, and frequently links the early church’s experience of persecution and suffering to sharing in Christ’s sufferings as well as in his glory. For St Paul, this is the normal Christian experience; and I would extend that to being the normal human experience. We all share in Christ’s suffering, and he shares in ours – I feel there must be an open wound in the very heart of God.

While God can work through our suffering to bring growth, we must be careful not to go either to the extreme of spiritual bypassing (whereby we avoid our negative feelings by telling ourselves not to get upset because it’s all part of God’s plan) or to the extreme of self-flagellation – life brings suffering enough on its own, we don’t need to add to it. And, of course, Jesus calls us to alleviate suffering wherever we can, to feed the hungry, clothe the poor, and visit those in prison – it is clearly not something to encourage or ignore.

At the end of our gospel passage, Jesus blessed his disciples and left them – at which point they were filled with great joy. There must have been great joy in knowing that God wasn’t demanding perfection through flawless adherence to the law, as they had been taught, but that God welcomes broken, messed-up, failures to join him in the adventure of life. There is great joy in knowing that suffering isn’t something alien to us that we need to resist, but that it is part of what makes us the complex, beautiful people that we are. It creates depth as it hollows us out and makes a space where God is freer to work. There is joy and freedom in realising that the places we considered broken, shameful and ugly are the very places where God works to bring forth beauty, courage, and compassion.