The following is a reflection on Matthew 13:33 that I gave in May 2023, inspired by the work of Robert Farrar Capon on the parables of Jesus.

About 20 years ago, I bought this book about the parables of Jesus. Since then, it has been sitting on my shelf, periodically inviting me to return to it: I know it is full of great wisdom, but it is hard to understand and even harder to explain to anyone else. I find that rather ironic, as the parables themselves can be like that. Rather than giving us doctrines set in stone for all time, Jesus gave us parables that are wide open to interpretation. So, when I saw the Gospel for today, I thought it was high time I made an attempt to share with you some of the wisdom hidden in this rather challenging book.

Oh, and just to add one more layer of complexity, today’s parables are about the kingdom of God. Jesus talked a lot about the kingdom of God, but never really defined it; here he gives us five images to consider: a mustard seed, some yeast, treasure, a pearl and a drag-net.

I’m going to look at just one of these images to see if we can shed any light on what Jesus meant: the parable of the yeast.

As I read it to you again, just notice what image comes to your mind: ‘The kingdom of heaven is like yeast that a woman took and mixed in with three measures of flour until all of it was leavened.’ What image does that conjure up in your mind? I see a rather domestic picture of a woman at home in her kitchen kneading a modest ball of dough ready for the family meal.

My husband bought a bread machine about a year ago. In typical fashion, I chastised him for the unnecessary purchase, but then, of course, I am the one who has ended up using it, so I can say with some authority that it takes 400g of flour to make our usual loaf.

The woman in the parable used three measures of flour, which doesn’t sound like very much, until we go back to the original Greek, where we discover that the word for measure is ‘sata’ and that three sata is a little over a bushel of flour – which, in today’s money, is 21kg of flour. Let that sink in, 21 kilograms. That’s enough to make 52 loaves of bread.

This is such a large quantity of flour, that we could understand it to represent the world, in fact it’s so disproportionately huge, that perhaps it represents the whole of creation?

Can you imagine trying to deal with enough dough for 52 loaves of bread by hand? It’s hard enough work kneading the dough for a single loaf, hence the aforementioned bread machine, but the mixing, the kneading, the handling of such an enormous quantity of sticky, heavy dough is a job for an industrial machine, not an individual person.

So, what might this tell us about the woman in the parable? Well, she has very strong arms and is extremely determined – despite the challenges of handling such an enormous quantity of dough, she gets the job done. This woman is far removed from the domestic goddess I had originally imagined!

What a fantastic image of God!

Not only is this one of those few female pictures of God hidden in the Scriptures, but it is a powerful one. God as a woman baker has a job to do and she is doing it with gusto. She has taken on a project that is not easy; the parallel between the unwieldy lump of dough and the current state of the world is obvious.

But back to the kingdom and what this parable can tell us about it.

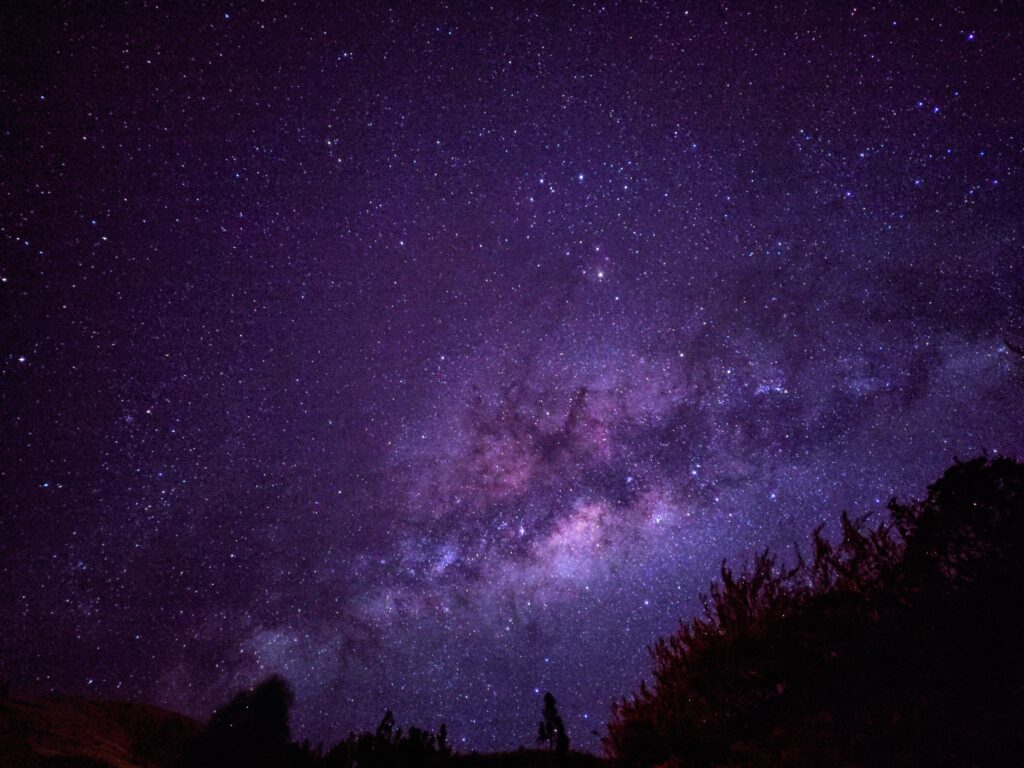

Firstly, the kingdom has always been there. No competent baker would add yeast part way through the process, it’s mixed in right at the beginning. Similarly, God’s kingdom has been at work ever since the very beginning of creation, right from the big bang. The kingdom didn’t start when the Word became flesh in Jesus, but in the person of Jesus, God showed us his face and told us his name and sent us out to share that good news with everyone.

Secondly, the kingdom is everywhere. The yeast isn’t reserved for a special portion of the flour, it’s mixed into the whole. The kingdom of God is seeded throughout the whole of creation, not just in the church or so-called Christian nations. God has done amazing things through the church and the world would be much poorer without it. As well as nurturing the spiritual growth of individuals, the church has a rich artistic and cultural heritage, and in many places it is a lifeline for struggling communities, and I could go on.

However, it is also true that God’s kingdom has not been limited to the activities of the church. Just as the yeast leavens the whole dough, God is also at work in the wider world – think of the wisdom of Buddhism or of indigenous communities, the creativity found in cultures very different to our own, and the amazing knowledge and insights gained by peoples all over the world. What is more, not infrequently, the church has been dragged kicking and screaming into the kingdom that God has already been advancing in the world; just as an example, we are rightly shocked that women didn’t get the federal vote until 1971 in Switzerland, yet in the Church of England, women had to wait until 1992 to be ordained priests, and 2015 to be ordained bishops!

Thirdly, just as the yeast cannot be separated from the flour, so God’s kingdom cannot be separated from the world. Which takes us back to the very end of our other reading this morning from the letter to the Romans.

For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Nothing can separate us from the love of God – it might not always feel that way, but God’s love is as inseparable from his creatures as the yeast is from the dough.

Fourthly and finally, the kingdom is mysterious. The Greek verb translated as ‘mixed’ in this parable actually means to hide: the woman hides the yeast in the flour. Once it’s in the dough, yeast is invisible to our eyes, but it is there quietly doing its work, slowly but surely leavening the whole batch. Similarly, we cannot ‘see’ the kingdom, or even define it, but we can see its effects: the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them (Mtt 11:5). God has hidden the kingdom in the world, he is transforming creation before our very eyes even though we cannot always see it.

We live in a time of great change, and our instinctive reaction is often fear. We see the decline of the church in the West and, understandably, lament. Is the yeast still leavening the dough?

Perhaps theologian Phyllis Tickle has something helpful to say about this. She points out that about every 500 years, the church goes through what she describes as a giant ‘rummage sale’ – what she means is that it cleans its house, which is a difficult process, but that something new emerges.

These ‘rummage sales’ are linked to what is going on in the wider culture and she cites the following events, each following on from the one before after about 500 years: we start with the incarnation of Christ, then the emergence of monasticism as the church went underground at the collapse of the Roman Empire, next the Great Schism that separated the church into the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox branches, and most recently the Reformation. We are now 500 years on from that, and the time is ripe for great change in the church again.

We don’t know what will come next, but we don’t need to be afraid: the yeast of the kingdom is slowly but surely continuing its work.

So where does this leave us? It seems to me that the overarching message is to patiently trust God. To trust him in that holy ambiguity that our chaplain talked about last week. He has been at work in the whole world since the very beginning, is at work now, and will continue his work until it is finished. We needn’t despair, because although it is often a mystery to us, the kingdom is growing. It isn’t something we can drive and still less something that we are responsible for, rather we are invited to join in with it. And I know that you are already joining in the work of the kingdom in many ways, through your friendships, families, work, voluntary activities and much more, both through the church and elsewhere. So I encourage us to keep I up the good work and be open to whatever else God might be calling us to do.

One last thought about this parable; the dough is indigestible in its current form, and it won’t be edible until the yeast has finished its work and the loaf has been baked. So too, our world is indigestible in its current form, there are so many things about it that outage and upset us, that cause us pain. Despite the unwieldy, almost impossible task, the woman baker of our parable got the whole dough leavened. Let us trust that God will similarly transform the whole world through the work of His mysterious kingdom.